Introduction

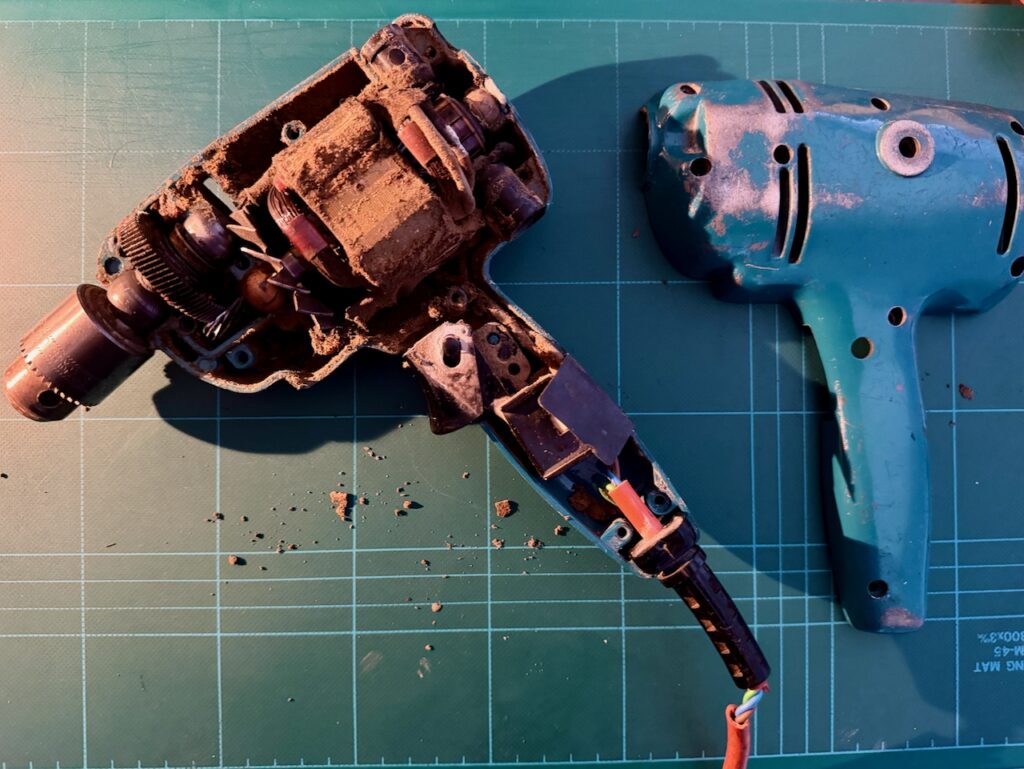

The Black and Decker Super D500 is a 1.5 amp 250W drill dating from the 1960’s. Lots of these must have been made as they seem readily available on eBay with prices from £13. I inherited this one from my father, and it hasn’t been used in many years. I recall as a child being the ‘gofer’ for him while he installed central heating, and re-wired houses. I have seen this drill through timber, concrete, brick (including Accrington brick – eventually) and metals – aluminium and steel.

The orange outer insulator of the mains cable is starting to perish, and has broken as it exits the strain relief. I don’t believe it has ever been opened up since it left the factory.

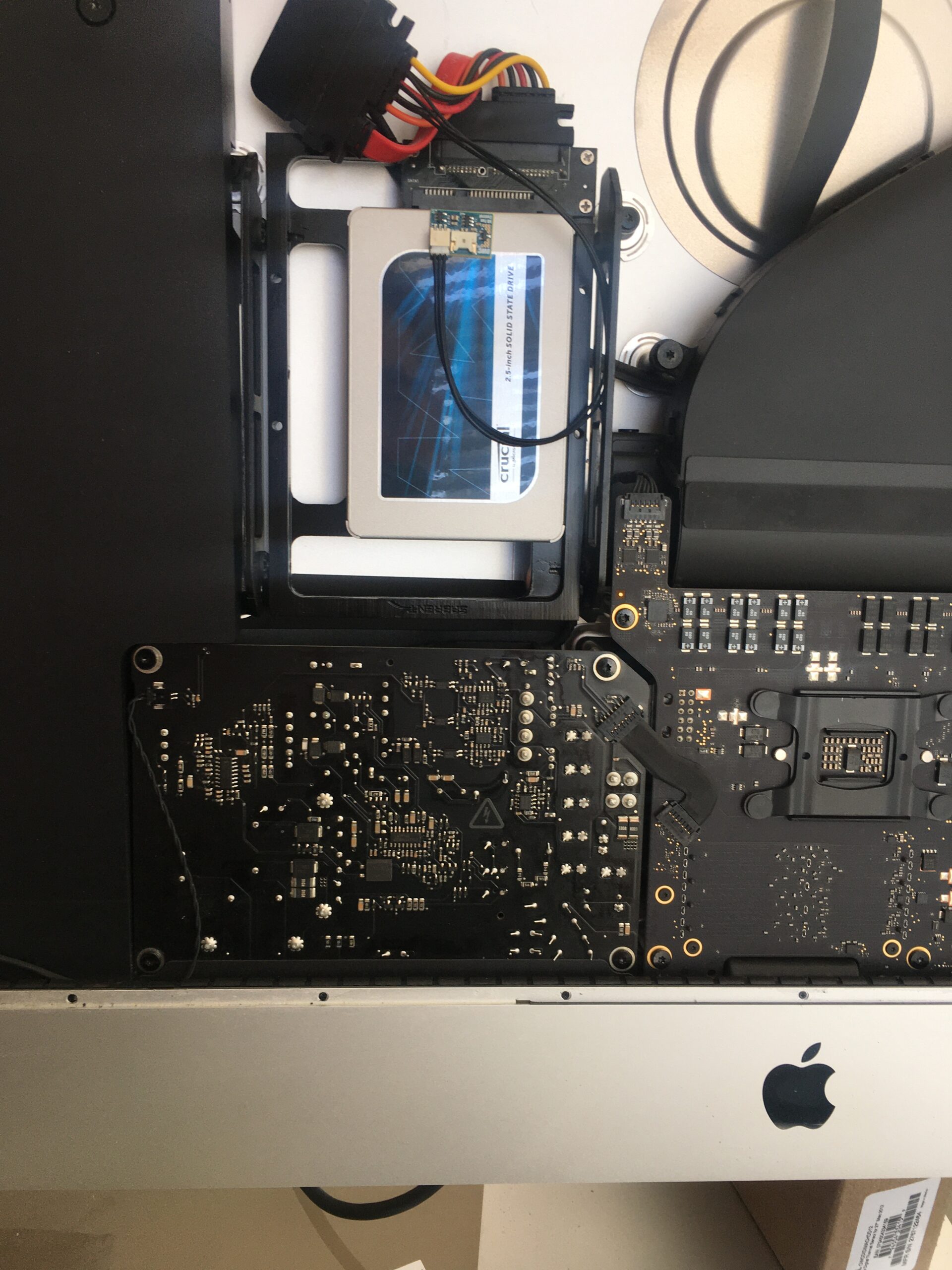

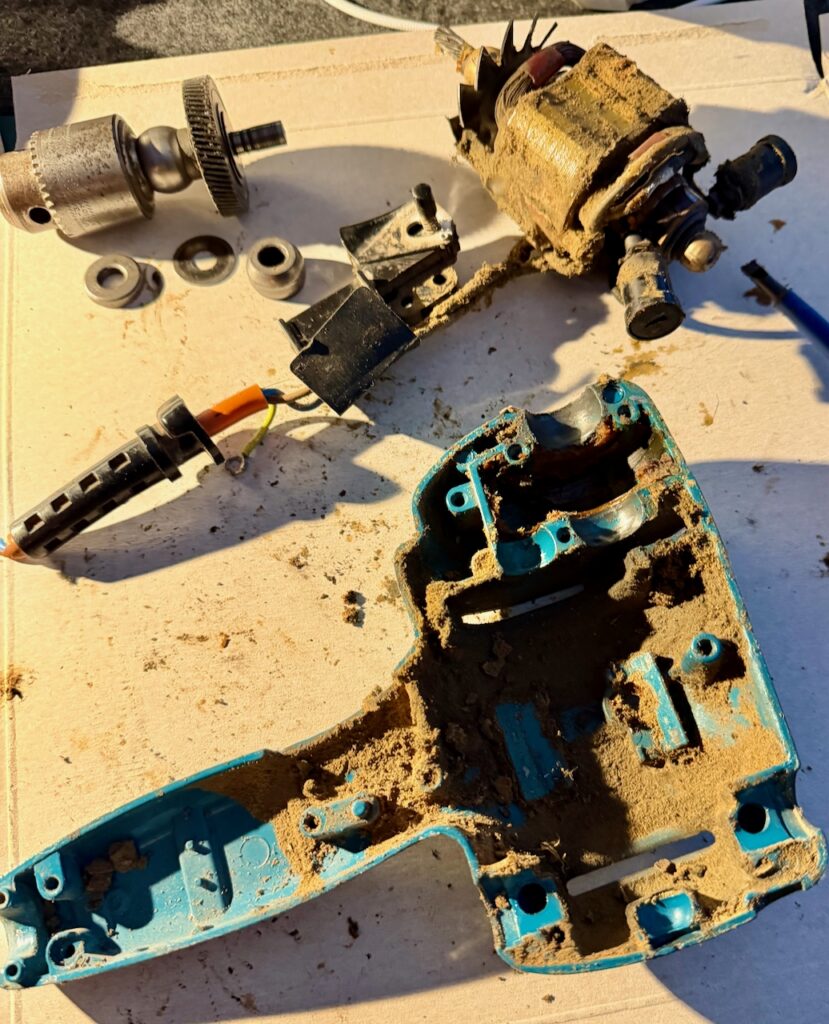

To get inside, the two halves are fixed together by 8 equal sized screws. As the drill is opened up, we can see that every internal surface is thickly coated with compacted dust of all the material types I mentioned earlier – particularly it seams, red brick. It fills the gear area, and motor, everywhere.

To ease things, I cut the mains cord, and removed the components from the back shell. They all simply lift out with no additional fixings.

Then, first before dealing with the cable replacement, the clean up. A screwdriver to release the worst of it, then a good squirt of isopropyl alcohol to further clean the surfaces.

The compartment containing the gear from the motor shaft to the chuck shaft was full of old, sticky grease – mixed with the same dust. This was all scooped out and again further cleaned with isopropyl.

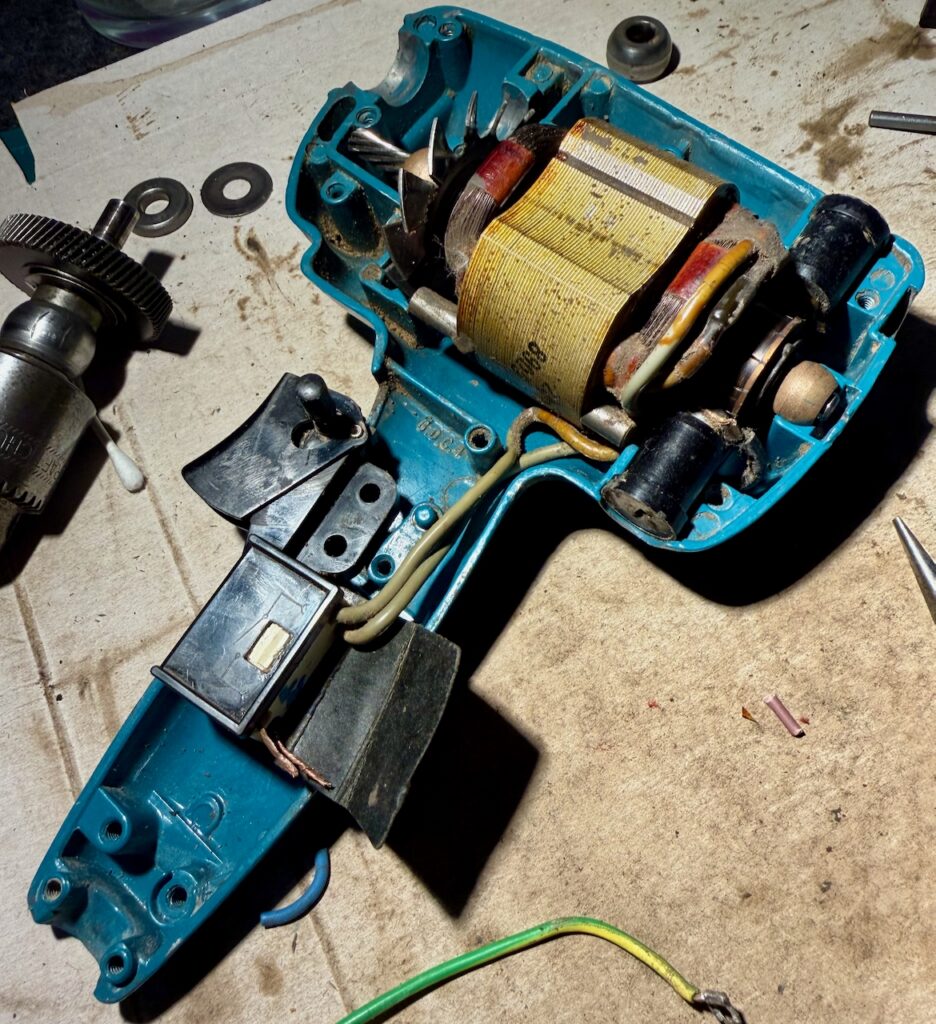

Taking care not to damage the wires, the dirt was cleaned from the motor, the brushes, the cooling blades and switch.

To re-use the strain relief meant removing the old cable. Very much easier said than done, as it felt very solidly stuck in there. First I cut it free from the other components, and pulled through each of the core wires, leaving only the orange sleeve. Since this was starting to perish, simply using long nose pliers pulled a bite out of the material, leaving the rest in place. I poked through the edge holes of the strain relief to try to separate the two materials. In what I think was a mistake, I cut through the thickest part of the relief, and eventually managed to pull the orange insulator free.

The new cable has a slightly smaller outside diameter than the original, and as we will see, it is important that the cable is gripped in-place by the strain relief. So, I gave it a few wraps of electrical tape inside the grip.

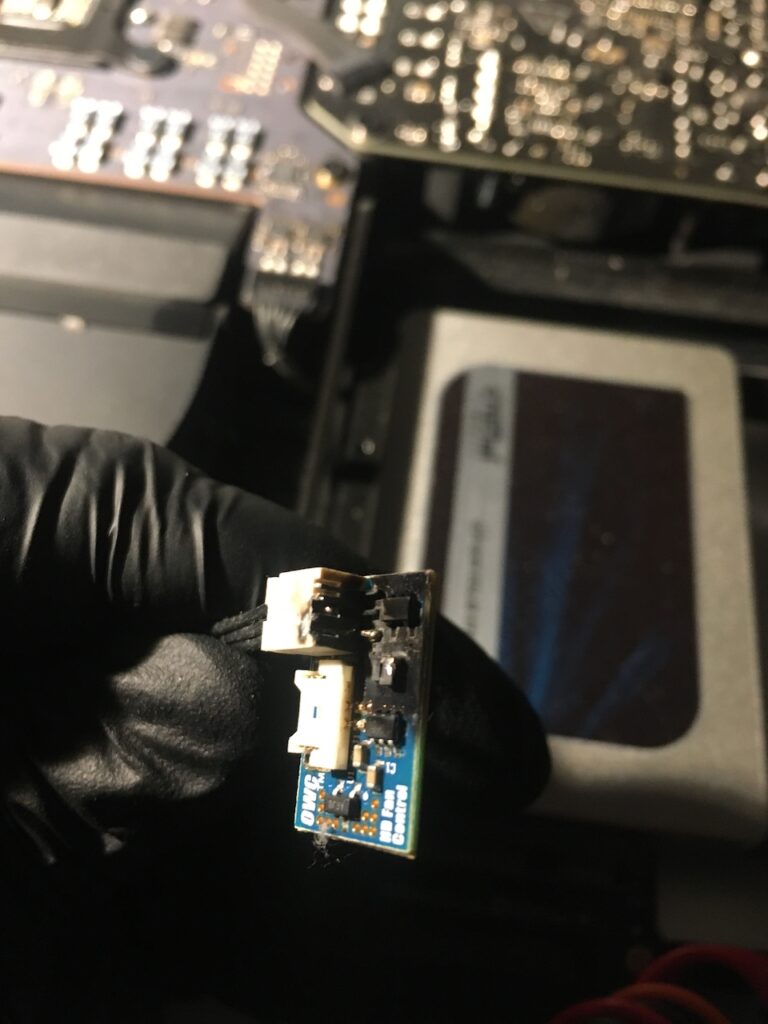

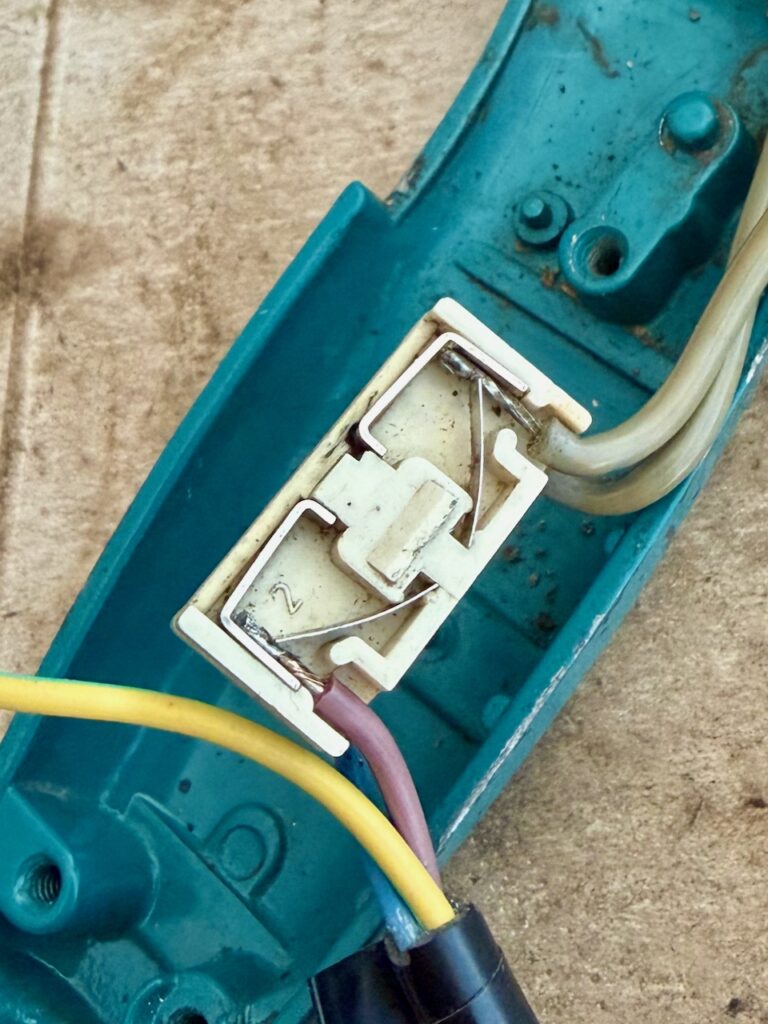

Connecting the new cable to switch RB1

I found myself disassembling the switch entirely since I couldn’t see how the wires were screwed into the terminals. That’s because they are not – they just need pushing in. To get the old ones out, just push a small screwdriver alongside the old wire to free it from the grip. Then push in the new wires. I think it is better if the wires are twisted and tinned with solder.

Warning if you decide to disassemble the switch. It contains springs and very small parts that can launch in many directions.

To separate the white connection block from the rest of the black switch, you can see that the white block has a lug each side. This does not move. To release the block, push a slim/small screwdriver between the outer shell and the block at the point of the lug. It is the outer black shell that must flex, not the inner white. Carefully pull out the white block, and be aware that the other parts are likely to fall or spring out.

The black frame includes trigger and lock-on mechanism that I left in place, then the rest of the switch is made up of a sled with two spring-loaded contacts, that is pulled by the trigger to make the circuit. In my case I could see that one of the sled contacts was showing signs of wear possibly from arcing. On the reassemble I decided to make that the contact for the neutral rather than live.

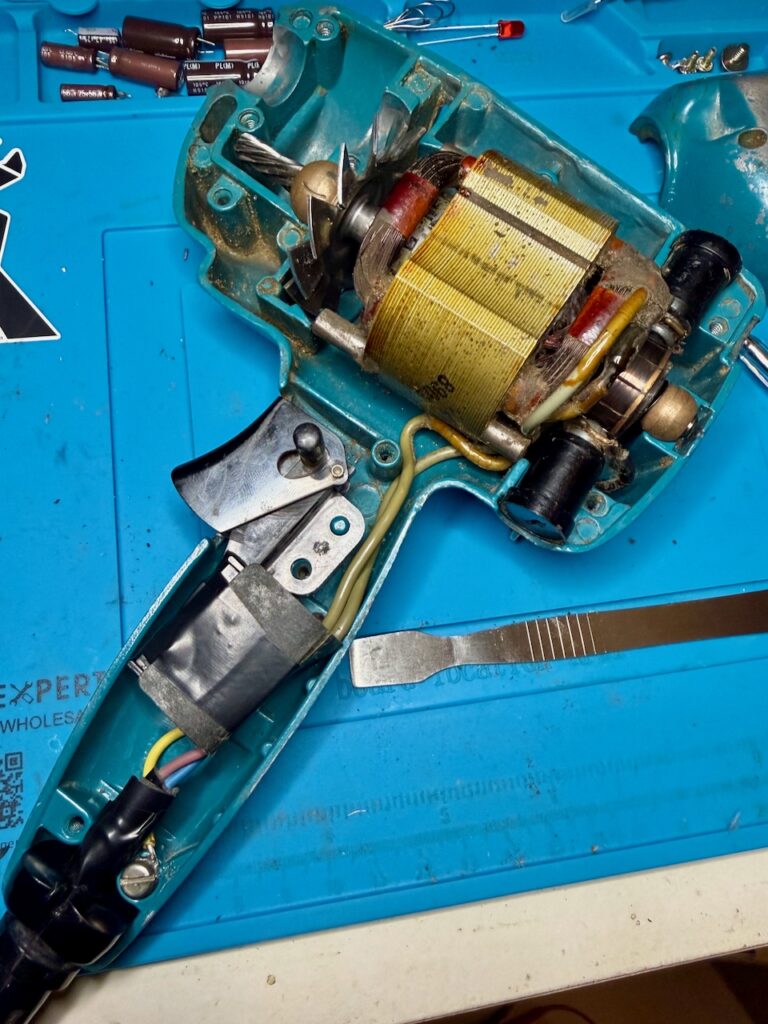

After cleaning, to reassemble, my steps were:

- Place the outer frame on its back and drop in the large spring, and the ball-bearing into the square recess

- Hook the sled with the trigger in the off position, and lower into the assembly, it should align such that the hole with the spring is over the ball bearing. Hold the sled in position without letting the bearing fall out of position and roll around

- Into the top side of the sled, drop in the two springs and carefully place the contacts

- keeping the sled in position, slide in the white contact block, along with the insulation wrapper (in my case I forgot the wrapper and rather than disassemble again, I secured it with electrical tape

- Once assembled, use a continuity meter to test the switch in open and closed positions

Reassembling the drill

A few drops of 3 in 1 oil in the bearings and the motor and and place all the components into the back shell of the drill.

Carefully secure the earth connection. There is a washer that I de-soldered from the old cable and soldered to the new before screwing to the metal shell.

Grease the main gear. I used a moly grease that was much less viscous, and needed less in quantity than the original grease – although I don’t know how much of that was through being old and contaminated. (I think I only used about 1g of the 500g tub.) Carefully rotate by hand to distribute the grease heavenly between the gears. I am not sure if this is the best grease to use for the long term, but this drill will only have light use for the rest of its time with me.

Ensure the carbon brushes are properly positioned. Then close the front shell, securing with the 8 screws.

Be sure to test before plugging into power:

- There is excellent continuity between the earth of the plug and all exposed metal of the drill. (The shell where the paint has worn down; the chuck, the screws

- Check continuity between live and neutral, that is open (no continuity) with the trigger in the off position and closed (continuity) when the trigger is pulled

- Check that there is no continuity between any of the metal parts and live or neutral for the switch in both positions

Plug in, it should work, sound, and smell a lot better than it did before!